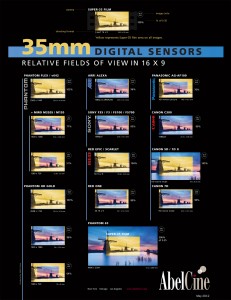

Digital Film – Sensor Size

Sensor (CCD) Size – Industry Name (example)

Sensor (CCD) Size – Industry Name (example)

– 51.2 x 28.8 mm – Phantom 65

– 36.0 x 24.0 mm – Full Frame (Canon 5D)

– 27.7 x 19.0 mm – APS-H

– 24.0 x 13.0 mm – Super 35 (Canon C100 / 300)

– 23.6 x 15.7 mm – APS-C (Nikon, Pentax, Sony)

– 22.2 x 14.8 mm – APS-C (Canon 60D)

– 20.7 x 13.8 mm – Foveon (Sigma)

– 17.3 x 13.0 mm – Four Thirds (Panasonic GH3)

– 15.8 x 08.9 mm – (Black Magic Cinema)

– 13.2 x 08.8 mm – Nikon 1/CX

– 12.4 x 7.02 mm – Super 16 (Black Magic Pocket)

Graphic by Abel Cine

Both Full Frame and Super 35 are based on the size of traditional 35mm film. However, full frame cameras have a much larger sensor where the height of the frame is equal to the width of a strip of 35mm film—the orientation is rotated 90 degrees. With Super 35, the sensor dimensions and orientation match that of traditional film.

While there is a lot of hype around the sensor size, a small sensor can produce in incredible image when the CCD (Charge Coupling Device) is scanned at a faster rate.

What’s more, larger sensor cameras invoke a more shallow depth of field, just like opening the iris (aperture) of a lens to its lowest setting (ie: f-stop 2.0). More light over a shorter period of time results in a shallow depth of field. Sometimes this is desirable, sometimes not.

Keep in mind that nearly every movie ever made was shot on 35mm film and in the past decade, nearly every digital film was shot using a camera which maintained a Super 35 sized sensor. Here is a good, historic overview of widescreen aspect ratios.