A mantra for the New Year

Seek intellectual stimulation.

Express creativity in multiple forms.

Promote science education as the best hope for the next generation.

Never stop learning or challenging the norms.

Seek intellectual stimulation.

Express creativity in multiple forms.

Promote science education as the best hope for the next generation.

Never stop learning or challenging the norms.

The Internet has failed to deliver what was promised over two decades ago. Or perhaps, we have failed to fully embrace that which it delivers.

We have at our finger tips facts, figures, and data. At any given moment, 24 hours a day we can validate and substantiate the tidbits of information which bombard us. We can negate rumours, stories, and marketing campaigns that tease our sense of logic or appeal to our emotional pleasures and fears.

Yet, we do not.

The Internet also delivers a kind of drug, an addictive substance which calls upon the very foundation of our DNA. We are drawn into conspiracies, twisted logics, and backward ways of thinking that support our innermost fears, the stuff that predates one or two generations as we give into eons of xenophobic behaviour.

While the spiritually minded speak hopeful of consciousness rising, I see instead the rise of the human species for who we are when the spiritually minded retreat to their havens of like-minded and similarly kind.

Perhaps some day the Internet will deliver an upgrade to humanity, a version 2.0 in which we care about the other as much as we do our own self. But for now, the beta release a few million years in the making will have to do.

I have a gift for you.

Something thin, transparent, yet powerful and strong.

It is able to block the most painful, invisible projectiles and

in the same moment, allow what is desired to enter.

It is neither supernatural nor entirely physical, … or perhaps it is both.

I have something for you, a gift that cannot be given, a source of tremendous power that is always within reach yet difficult to receive.

The gift is you.

Every time we accept a rule or a guideline without asking Why?, we give into someone else’s power. Every time one group of people is told they don’t belong because of their beliefs, we have used religion as a means of controlling how people think and behave, isolating rather than uniting.

A belief is a powerful motivator, a means to drive one forward through challenging times, to unite individuals in a common goal, for multiple generations. Yet, a belief is nothing more than a thought process, nothing more than an electrochemical pattern in one’s head. It cannot be proven nor denied, therefore it should never, ever be used to conquer and divide.

When she secures home to her back,

and moves from red desert to blue mountain,

she will find comfort in what was left behind.

For through mobility comes the discovery,

that home is not a place

but a state of mind.

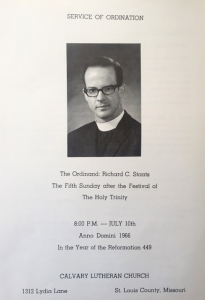

I grew up a PK, a preacher’s kid. Saturday nights my father sat at the kitchen table with one, two, sometimes three consecutive bowls of ice cream to fuel the hand writing of his sermons for the next morning. Draft after draft on a yellow note pad, his crisp printing of a style I yet wish I could mimic. Drawing from the unfolding events of the prior week, in our own community or across the nation, my father told stories which captivated those who attended the service, bringing them to focused place and time where ancient history found relevance in our modern world.

I grew up a PK, a preacher’s kid. Saturday nights my father sat at the kitchen table with one, two, sometimes three consecutive bowls of ice cream to fuel the hand writing of his sermons for the next morning. Draft after draft on a yellow note pad, his crisp printing of a style I yet wish I could mimic. Drawing from the unfolding events of the prior week, in our own community or across the nation, my father told stories which captivated those who attended the service, bringing them to focused place and time where ancient history found relevance in our modern world.

The simplicity of the connections he drew were easy to understand. The characters he brought to life, both biblical and modern, were memorable. He never hid behind the pulpit, but walked among those who came to listen, engaging in a kind of two-way interaction that was both subtle and meaningful, even if his audience was mostly silent. The stories carried messages easily interwoven in our every-day lives.

We moved frequently, a half dozen times in twenty odd years. My brother and I embraced a father whose time and attention was most often devoted to serving those in need. Growing up I was sometimes asked if I would follow in my father’s footsteps, embracing a life in the church. My answer was, “Most PKs either rebel or yes, follow suit. I find myself in the middle.” But now, my response would be that I cherish what I have gained from being the son of a minister, for I have learned what it means to be selfless, at times putting others’ needs before my own.

Therein lies the real blessing of a life of servitude–putting others’ needs before your own, devoting your life to causes which challenge the political, economic, and social norms. My father protested the Vietnam war, worked with the Sanctuary movement in the 1980s, and within the City of Phoenix to better understand the homeless and the poor. He is a regular contributor to the Arizona Republic newspaper on issues of human rights and political arenas, and has worked tirelessly to improve his own neighborhood through research and planning for improved street safety and sense of community.

Therein lies the real blessing of a life of servitude–putting others’ needs before your own, devoting your life to causes which challenge the political, economic, and social norms. My father protested the Vietnam war, worked with the Sanctuary movement in the 1980s, and within the City of Phoenix to better understand the homeless and the poor. He is a regular contributor to the Arizona Republic newspaper on issues of human rights and political arenas, and has worked tirelessly to improve his own neighborhood through research and planning for improved street safety and sense of community.

With two masters degrees and eight years experience as a social worker, my father has seen a diversity of humanity. He has performed countless marriages and funerals, welcoming those new to life on this planet and helping find closure for the families and friends of those who have departed. He managed an adoption agency for a half dozen years and has been witness to the pain and suffering of an often confusing world, in an era when suicide took the lives of farmers who lost their land. My father has helped many to celebrate the cherished moments in life, to learn to communicate when it seemed relationships were destined to fall apart.

But his lasting legacy is his nearly 30 years dedication to giving a safe haven for the LGBT community. When in 2014 Joe Connolly and Terry Pochert filed law suit against the State of Arizona, and won, they credited my father for having given them support, for accepting them in the church family, and for encouraging them to pursue their legal acceptance as a married couple.

Fifty years ago today my father was ordained a Lutheran minister. He walked away from a likely career as a PGA golfer and his university education in mathematics to pursue a life of serving others. While his skills are many, including carpentry, writing, cooking and baking, it is his relentless pursuit of finding justice, acceptance, and peace for those within his reach that I cherish as the most valuable asset to carry with me.

Once again, I have moved into the forest.

The place where I am most at home, where each hour of each day is mine to own.

Into the forest and the distant, chaotic heart beat of the city is but a fading memory.

Here, the only sounds are those over which humans have no control.

We cannot stop the aspen from quaking, the thunder from shaking, nor the rain from falling.

Into the forest and I feel I am once again … home.

For the first time in four years, I enjoyed a weekend at Joshua Tree National Park. I longed for this time, to return to one of my favourite places in the world. I walked by moonlight, climbed by daylight, cooked simple meals made from simple foods, and slept under a cloudless, star lit dome.

For the past two years living a suburban life in South Africa, and now, temporary residence in Phoenix, I struggle to find satisfaction in the simple things. Cities have a way of drawing us into complex patterns, escalating, upward spirals of complexity. Joshua Tree provided fresh reminder of what it means to live simply.

Living in the city too can incorporate many of the joys of a simple life–growing herbs, tomatoes, squash, and peppers in the space between our buildings, roof-top gardens or window boxes, cooking meals at home, even sleeping out of doors where afforded. But there must be something else, something more we all desire, for so many of us choose to sleep in a tent, cook over a wood fire, and find a different kind of comfort in living with less, even if for just a few days.

Five gallons of water for two people for three days. Two cups of white gas for six meals. A loaf of bread, a tin of hummus, oatmeal, cucumbers, and that was all that was needed. Simple foods, simply prepared. The enjoyment of those flavours was of course, far more nourishing than any restaurant or take out dining.

This is a frame of mind, not a location or special space. Can we learn to take it with us, no matter where we reside?

Other essays in What I learned from the Road

I am an unknown actor

playing an inconsequential role,

in a production which has no author.

An invisible stage crew,

wearing clouds so as not to be seen,

has elevated this narrow stage to an unnatural height.

Here I witness the moon,

as a canned light hung from a hidden catwalk,

burning to bring us the night.

The chair on which I rest shudders with vibration,

a massive engine suspended from the adjacent wing

which folds only once with the closing act.

The light of the Moon comes to me twice,

once from its refractive regolith,

then again from the curve of the nearby, rotund shroud.

Internal blades spin with incredible precision at an incomprehensible velocity so as to maintain this airborne guild. With me, there are three hundred actors. I am but twenty seven and one. Together, we long for an audience which cannot attend yet will embrace us individually, at theatre’s end.

What have we done, a species so skilled in creation having fabricated such unnatural settings?

What are we doing, creating discontinuity in the name of modernity?

What will we become if we continue to embrace a life disconnected from what we know is life sustaining?