New Years in the Grand Canyon, 2026

Colleen and I engage in an outdoor adventure each New Year, backpacking in Hawaii or the Superstition Wilderness, or rock climbing in Joshua Tree National Park. This year we chose to return to the Grand Canyon. Three years ago we ventured down the incredibly challenging Nankoweap trail, from the North Rim of the Grand Canyon to the Colorado river, 32 miles and some 13,000 feet total elevation change, six days and five nights. We had hoped to do this again, but due to the massive fires that destroyed the north rim lodge and tens of thousands of acres of forest, the trail remains shut down. In a conversation with a back country ranger we learned about the eastern reaches of the South Rim of the Park, and an opportunity to explore something new.

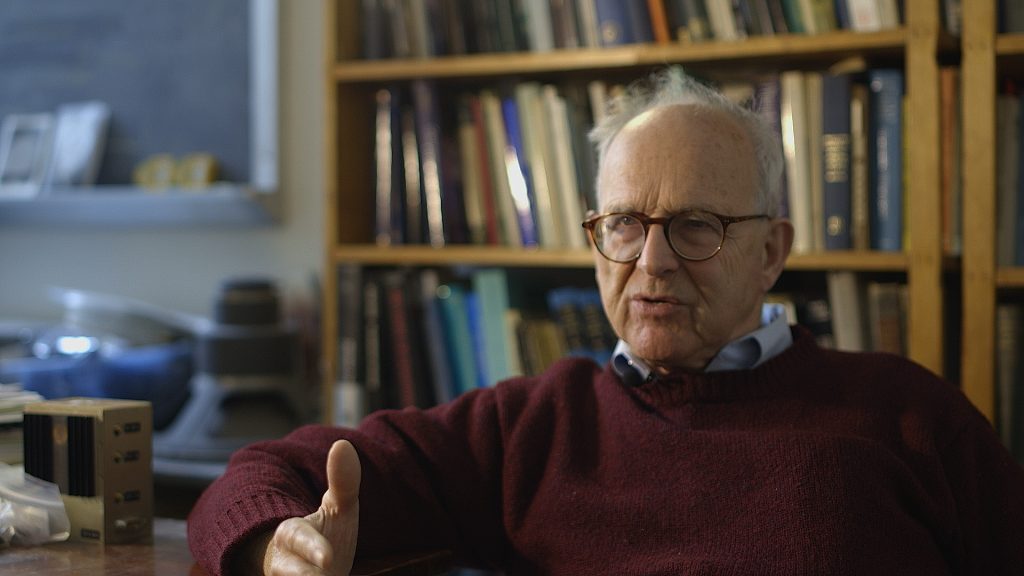

On December 30 we left our car at roughly 11:15 am and ventured nine miles down the Tanner trail, from rim to river. We arrived to the campsite an hour before sunset at 4:30 pm. We camped at Tanner Rapids for two nights, enjoying a chance for our legs to recover and to celebrate the New Year with the bold sound of the Colorado taking us to sleep, then greeting us each morning. That first night we enjoyed conversation with four Flagstaff teenagers who venture to the Grand Canyon on a regular basis, over weekends and school breaks. Clearly, they are experienced and comfortable in this environment, thinking nothing of a 20-40 mile venture over a long weekend. One of the four, Cruz, is an intelligent, inquisitive, fully engaging young man who expressed interest in our expedition tent, asking myriad questions about our gear, the places we had explored, and about our work and aspirations. It was a truly fun conversation, and remarkable in that he actually asked questions—a nearly lost function in the youth of his digital generation. Thank you.

On the third day we repacked our gear and hiked east on the Beamer trail to the Little Colorado River (LCR), stopping a half mile shy on the boundary of the Navajo Nation. This was by no means an easy walk. We traversed 26 (yes, we counted) side drainages over roughly five miles, in and out of ravines both shallow and deep, some requiring some effort to navigate the boulders and pour-overs with cairns (trail markers) difficult to locate.

We arrived late afternoon and camped on a sandy knoll, a relatively small outcropping with just three or four spots for a tent. After setting up our tent on the sand, with ropes tied to rocks and driftwood to brace for the predicted storm, we jogged back up to the trail and to the LCR overlook. Deep into dusk, with limited light remaining, the turquoise blue water gave us the sensation of having found our way to magical wonderland, and we eagerly awaited the morning.

We packed a day bag with food, water, first aid, and rain shells and returned to the LCR, exploring the right bank (hiking up the river) for roughly a mile. We enjoyed a scramble along precarious sandstone ledges, some a thin blade that looked as though it might crack under our weight. But others before us has placed stone stairs and cairns, giving us the confidence to follow.

The blue water was captivating, with a subtle smell of sulfur and a sense of warmth, perhaps associated with the associated odor of hot springs more than the actual temperature. The color contrasts, from blue to white to red and green was surreal. I knew I could not fully retain the images I was seeing, nor did our camera due justice to the artist’s pallet before us. Nonetheless, we took it all in, speaking excitedly about a return with pack rafts and chance to paddle the lower section of the LCR to the confluence, then down the Colorado for eight miles.

The trail was littered with animal droppings from deer or sheep, we didn’t know. But just as we returned to the confluence a mule deer, healthy and strong, bounded before us, looking back over her shoulder before disappearing into the brush. A river trip pulled up and explored the opposite shoulder of the LCR, just one hundred meters or so before returning to their boat. We later exchanged New Year greetings as they rowed past our campsite, down stream. We had wanted to ask for a beer, a common exchange on the river, but noted they were avoiding the strong eddy that sat between their boats and us, just off the beach where we stood and waved.

The trail was littered with animal droppings from deer or sheep, we didn’t know. But just as we returned to the confluence a mule deer, healthy and strong, bounded before us, looking back over her shoulder before disappearing into the brush. A river trip pulled up and explored the opposite shoulder of the LCR, just one hundred meters or so before returning to their boat. We later exchanged New Year greetings as they rowed past our campsite, down stream. We had wanted to ask for a beer, a common exchange on the river, but noted they were avoiding the strong eddy that sat between their boats and us, just off the beach where we stood and waved.

We shared the campsite with four individuals from Nantucket the first night, then had it to ourselves the second. I took a bath in the Colorado River, which was truly exhilarating. The rain came, not heavily, but enough to turn the LCR from blue to brown, and increase the Colorado’s flow by the next morning. The water was a good two feet higher on the beach, again touching the drift wood where it had deposited it some time before.

The hike back to Tanner Beach felt good for the first four or five miles, but became harder as the sun moved from overhead to the west, forcing us to remove layers. Hiking in a T-shirt in December isn’t right, it’s just not right, and we were still sweating. We discussed how we frequently run nine miles (or more) out the back door in Cascabel, through river beds filled with sand and cobbles, but the same distance with 35-40 pound packs is a different journey altogether.

We briefly met the Nantucket crew again, then continued to the far western edge of the Tanner peninsula where the Colorado turned south for just a few hundred meters, then west again through a small rapid. The beach sand was fine, soft, and warm between our toes even as the wind was chill and the water cold. We set our tent beneath the branches of a mesquite (or cat claw, I am not certain) and fixed our last dinner on the trail. We always bring at least one extra hot meal, but had consumed it two days prior as a reward for our hard work, and to put extra calories into our bodies, a much needed boost after burning more than we consumed for the first five days.

I stayed outside the tent for an extra hour and a half, photographing the Moon as it rose over the cliffs, Jupiter and two of its moons (although this particular Canon Powershot is not ideal for night exposures), and even a rocket launch with the tell-tale flairs from its rocket engines. The rock bed on which we camped was like nothing I had ever seen. At first glance, it was just a gravel bar. But upon closer inspection I noted that every single stone was partially cemented to the sand beneath. This appeared to be a conglomerate in the making, a stable, solidifying mantel despite the lack of overlying pressure, heat, and time. There was a chemical and physical process occurring that created the illusion of every stone being hand-placed, as though some master mason had a vision for a palace floor, each a puzzle piece sitting exactly where intended. I need to learn more, to understand how this occurs and how long it will last. I walked carefully, flat foot to flat foot without the normal rocking from heel to toe so as to not disturb the bed behind me as I explored.

I stayed outside the tent for an extra hour and a half, photographing the Moon as it rose over the cliffs, Jupiter and two of its moons (although this particular Canon Powershot is not ideal for night exposures), and even a rocket launch with the tell-tale flairs from its rocket engines. The rock bed on which we camped was like nothing I had ever seen. At first glance, it was just a gravel bar. But upon closer inspection I noted that every single stone was partially cemented to the sand beneath. This appeared to be a conglomerate in the making, a stable, solidifying mantel despite the lack of overlying pressure, heat, and time. There was a chemical and physical process occurring that created the illusion of every stone being hand-placed, as though some master mason had a vision for a palace floor, each a puzzle piece sitting exactly where intended. I need to learn more, to understand how this occurs and how long it will last. I walked carefully, flat foot to flat foot without the normal rocking from heel to toe so as to not disturb the bed behind me as I explored.

The next day we rose early, ate a hot breakfast, and packed as the sun rose. Oatmeal with dried bananas and the last mangoes slices before we headed back up to the South Rim. Nothing about this nine miles and nearly 5000 feet elevation gain was easy. One foot in front of the other, a steady climb to the top, we took numerous breaks. I usually enjoy these efforts, a chance to focus my mind on designs, stories, and future plans but that day, for reasons I don’t understand, I was plagued by a relentless streaming of music in my head, and conversations without resolve. I could change the channel, but not the volume. It was, for me, more exhausting than the physical effort and without end until we reached the car. The parking lot was full, the sun warm on our arms, neck, and faces but the air cold. The car started, which is always good, and we drove to Cameron to stay the night in the lodge.

Yes, we could have carried lighter packs—we could have left the two books, Sierra Designs expedition tent, deck of cards, first aid kit, and extra batteries for our headlamps behind; we could have brought two 32F sleeping bags instead of a 0F and 32F which we frequently combine for a shared, warm cocoon. But the last time we were in the Grand Canyon it was far, far colder, too warm, in fact, which is good reason to worry, for us all. Physical challenge is the mental challenge, both welcomed by anyone who ventures into the belly of the Earth for more than a casual stroll.

The Grand Canyon never fails to engage, challenge, and reward. I came away with a hundred questions about geology, hydrology, and plant biology which will take a while to answer. Captured here, in these photos (below) are some of the beautiful things and some of the mysteries we desire to remember.