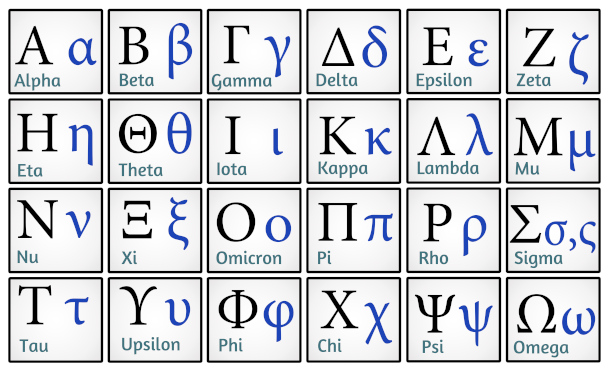

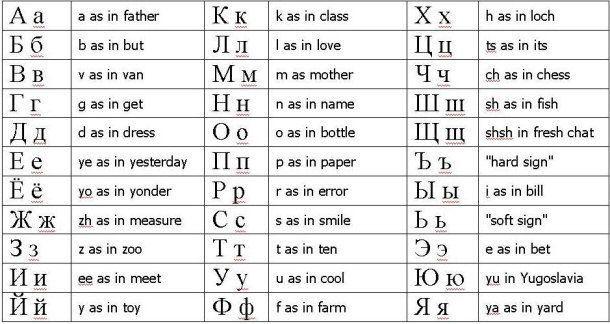

Colleen and I realized early in our stay in western Mongolia that learning the Cyrillic character set was necessary in order to communicate in Kazakh with any degree of functionality. It felt daunting to rewire our brains to accept new sounds associated with several otherwise familiar characters, and to learn new characters too. But there was a turning point when I realized that Cyrillic is based on the Greek character set, with some modifications. This at least laid a foundation of familiarity, and when compared from Greek to Cyrillic, made sense for both shape and sound.

What’s more, if you were to take each sound in the English language and assign a unique letter such that each letter has (with a few exceptions) one sound and each sound has only one letter—you have, essentially, Cyrillic. This is why there are 42 characters, many more than the 26 characters in the Latin character set for English. This actually reduces confusion once you get the hang of it. The Wikipedia articles for Cyrillic and Kazakh share a great deal more.

In relatively short order, truly just a half dozen hours of study over the first two weeks, we were able to read (even if sounding out new words one letter at a time) and with some challenge write the Kazakh language. It was, for me, thrilling to know that my passion for learning languages was in no obvious degree hindered by my age. In fact, learning to read and write a new character set seems to have built a stronger foundation for the vocabulary. That said, Colleen gained a larger vocabulary than I did, and very quickly too, which was simply enjoyable to behold. I was more fascinated by and engaged in the written characters and history, while Colleen could hear a new word just once or twice and integrate it into her vocabulary. After a few weeks we were able to say and receive the common greetings, ask basic questions, count change, and pick out key words in informal conversation.

The use of Google Translate was valuable in that it allowed us to convey complex concepts (English to Kazakh). Most of our host family members, co-instructors, and community organizers were also using Google Translate (Kazakh to English). However, the number of times it was wrong, and I mean hilariously, completely wrong was fascinating. I found that writing with pen and paper in a notebook was far more effective for two reasons: it forced me to conduct a more thorough translation with both Google Translate and one of the two printed dictionaries we brought with us; and by writing the Kazakh words in Cyrillic I was actually learning the language, not just pressing a button on my cell phone and forgetting what had been transcribed a few seconds earlier.

There is no short cut, no easy way around it—if you want to learn to read, write, and speak a new language, you have to just do it!